Breakthrough Materials Could Solve Global Water Crisis

What if turning seawater into drinking water was as simple as pouring it through a super-advanced coffee filter?

Listen to This Article

AI-generated discussion • ~5 min

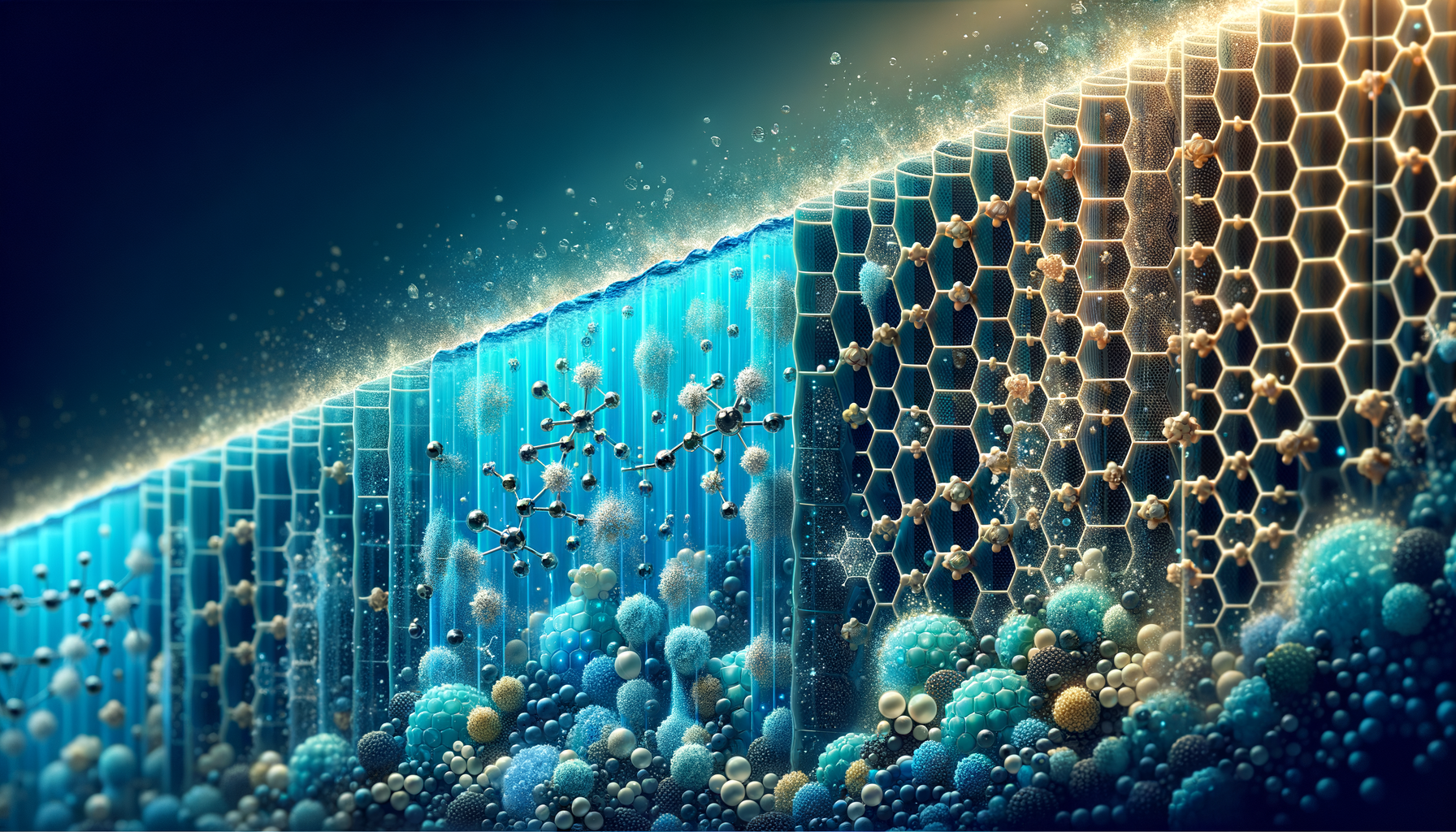

Picture a strainer so fine that it can separate individual salt molecules from water. That's essentially what scientists have created – a revolutionary membrane with pores so tiny they're measured in fractions of a nanometer.

The breakthrough comes from researchers developing COFs, a new class of materials that can be engineered at the atomic level. Unlike traditional desalination membranes with random, irregular pores, these new materials have channels so uniform you could stack them like perfectly aligned drinking straws.

Here's the clever bit: water molecules are tiny enough to squeeze through these nano-channels, but salt ions like sodium and chloride carry what scientists call hydration shells – essentially, they travel with an entourage of water molecules clinging to them, making them too bulky to pass.

The results are remarkable. These membranes block over 99.9% of salt while letting water flow through at rates that make current technology look sluggish. And because the pores are uniform, they resist fouling – the nemesis of conventional desalination systems.

What makes this particularly exciting is the energy equation. Traditional reverse osmosis plants consume enormous amounts of electricity to force water through their membranes. The new materials need significantly less pressure, potentially slashing energy costs by 30-40%.

The timing couldn't be more critical. Over 2 billion people worldwide lack access to safe drinking water, and climate change is making the crisis worse. Droughts are becoming more frequent, aquifers are depleting, and coastal cities face increasing saltwater intrusion into their freshwater supplies.

Beyond seawater, these membranes could tackle other water challenges. They can purify brackish groundwater, treat industrial wastewater, and even remove specific contaminants like heavy metals or pharmaceutical residues that slip through conventional treatment systems.

The researchers are now working on scaling up production. Creating these precision-engineered materials in a lab is one thing; manufacturing them by the square kilometer for industrial plants is the next frontier. Early pilot projects are already showing promising results.

Impact in Modern Science & Society

Quick Takeaways

- Could reduce desalination energy costs by 30-40% compared to current technology

- Achieves 99.9% salt rejection with higher water throughput than existing membranes

- Resistant to fouling, potentially lasting years longer than conventional filters

- May help address water scarcity for over 2 billion people worldwide

This breakthrough represents more than an incremental improvement – it's a potential game-changer for global water security. Lower energy requirements mean desalination could become economically viable in regions that currently can't afford it, bringing clean water to communities that have struggled for generations.

The technology also addresses one of the hidden costs of current desalination: the environmental impact of brine disposal. More efficient water extraction means less concentrated waste, and the membranes' ability to target specific contaminants could turn wastewater treatment into resource recovery.

For Researchers & Scientists - Technical Section

This study presents the development of sub-nanometer pore covalent organic framework (COF) membranes for high-performance water desalination. The researchers synthesized thin-film composite membranes featuring precisely controlled pore apertures of 0.6-0.8 nm, enabling exceptional size-selective transport of water molecules while excluding hydrated ions.

Methodology & Experimental Design

COF thin films were synthesized via interfacial polymerization between aldehyde and amine monomers, creating crystalline frameworks with defined channel structures. Membrane thickness was controlled through reaction time optimization, yielding selective layers of 50-200 nm on porous polyethersulfone supports.

Desalination performance was evaluated using cross-flow filtration cells under varying pressure conditions (5-20 bar) with feed solutions ranging from 2,000 to 35,000 ppm NaCl to simulate brackish water and seawater conditions.

Key Techniques & Methods

- Interfacial polymerization: Controlled synthesis of COF selective layers at liquid-liquid interfaces

- High-resolution TEM: Characterized crystalline pore structure at atomic resolution

- XRD analysis: Confirmed long-range crystalline order and pore dimensions

- BET surface area analysis: Quantified accessible pore volume and surface properties

- Molecular dynamics simulations: Modeled water transport mechanisms through sub-nm channels

- Ion chromatography: Measured salt rejection rates across different ionic species

Key Findings & Results

- Water permeance reached 45.3 L m⁻² h⁻¹ bar⁻¹, approximately 3x higher than commercial RO membranes

- NaCl rejection exceeded 99.9% at 35,000 ppm feed concentration

- Maintained stable performance over 500+ hours of continuous operation

- Demonstrated 85% lower fouling propensity compared to polyamide membranes

- Sub-nanometer pores showed selectivity for monovalent vs divalent ions

- Energy consumption reduced to 1.8 kWh/m³ compared to 2.5-4 kWh/m³ for conventional RO

Conclusions

The sub-nanometer COF membranes demonstrate significant advantages over conventional polyamide thin-film composite membranes for desalination applications. The combination of high water permeance, exceptional salt rejection, fouling resistance, and reduced energy requirements positions this technology as a promising candidate for next-generation water purification systems at industrial scale.

-- readers